Thursday, August 25, 2022

Dave Wilson and the Improved Safety Bicycle Part 2: Outriggers

Sunday, August 21, 2022

Dave Wilson and the Improved Safety Bicycle Part 1

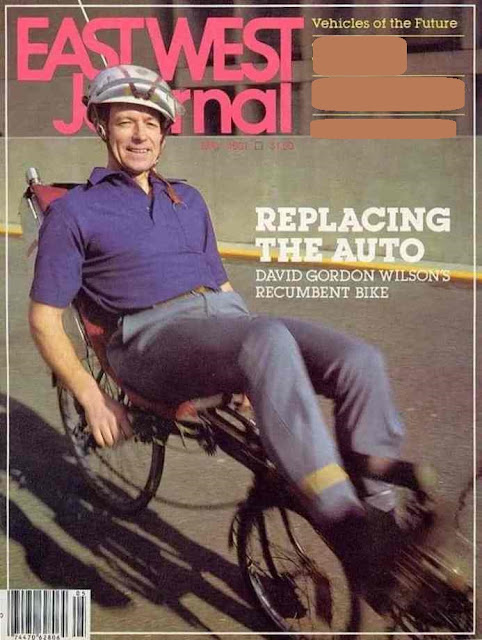

We can consider the late Prof. David Gordon Wilson, emeritus professor of mechanical engineer at MIT and author of four editions of Bicycle Science, the technical bible for all-things bicycle, as the father of the modern recumbent bicycle.

Wilson was a life long bike commuter and environmentalist and rode a small-wheeled Moulton to work. When Wilson launched his bicycle redesign competition in 1967, his goal was to encourage the development of a safer bicycle.

http://lefthandedcyclist.blogspot.com/2019/10/david-gordon-wilson-father-of-modern.html

With Fredrick Willkie, Wilson developed the Wilson-Willkie recumbent.

The Wilson-Willkie received national exposure when it was featured in a Mobil Oil commercial in 1976.Friday, March 19, 2021

The Podbike and the Quadracycle Quandary Part 1

Sunday, May 10, 2020

Velomobiles, E-trikes and the Transportation Infrastructure

It has been forty years since the Reader's Digest Magazine published this digest of a New York Times article from August of 1980. That summer, at the International Human Powered Speed Championships, a streamlined tandem tricycle, the Vector, was the first human-powered vehicle to break the 60mph barrier for a flying 200m speed run. But what captured the media's attention was that same tandem trike was pedaled from Stockton to Sacramento California on Highway 5 covering 41.8 miles at an average speed of 50.5 mph. Finally, it seemed that streamlined human-powered vehicles could provide a viable, healthy alternatives to the automobile.

It has been forty years since the Reader's Digest Magazine published this digest of a New York Times article from August of 1980. That summer, at the International Human Powered Speed Championships, a streamlined tandem tricycle, the Vector, was the first human-powered vehicle to break the 60mph barrier for a flying 200m speed run. But what captured the media's attention was that same tandem trike was pedaled from Stockton to Sacramento California on Highway 5 covering 41.8 miles at an average speed of 50.5 mph. Finally, it seemed that streamlined human-powered vehicles could provide a viable, healthy alternatives to the automobile. Friday, October 25, 2019

David Gordon Wilson: The Father of the Modern Human-powered-vehicle Movement

Prof. David Gordon Wilson died on May 2nd 2019 at the age of 91. He began the modern human-powered-vehicle movement when he sponsored a design competition for an improved version of human-powered land transport in 1967.

Wilson received his PhD in mechanical engineering from the University of Nottingham in 1953. Between that time and 1966 when he joined the faculty of MIT in 1966, he engaged in multiple pursuits.

He received a Commonwealth Fund Fellowship to conduct research in the USA with MIT an Harvard concluding with work for the Boeing Commercial Airplane Company as a gas turbine engineer.

Wilson did a two-year stint in Africa, teaching at he University of Ibadan in Ziria. Nigeria.

After doing two years of Voluntary Service in Cameroon, Wilson contracted malaria and was forced to more back to England.

In 1960, he was invited to be the technical director of the Northern Research and Engineering Corp to form a London branch specializing in turbo-power machinery and heat transfer.

Invited to MIT for a permanent position in 1966, Wilson taught thermodynamics and mechanical engineering. Students he advised conducted research in turbo-machinery, fluid mechanics and other design topics.

Wilson retired from MIT in 1994 after 28 years. He acted as professor emeritus until his death.

Outside of the university he pursued issues as an environmental activist particularly in regard to transportation. Wilson was appointed to a commission of the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. He served on the Center for Transportation Studies. He joined the Massachusetts chapter of Common Cause and was the co-founder of the Massachusetts Action on Smoking and Health which advocated for the rights of non-smokers.

In later years Wilson invented a heat-exchanger and a micro-turbine which are fundamental to non-photo voltaic solar power production. The company, Wilson Turbo-power was formed to commercialize the inventions.

And in 1974, Wilson came up with the idea of the Carbon Tax.

Of course, when it comes to the environment and responsible transportation, Wilson will be most remembered as a life-long commuter cyclist who used a bicycle instead of an automobile. Wilson was not deterred from using bicycle by the most severe weather.

Up until the mid 70's, Wilson rode a Moulton. Now at the time the Moulton design was quite sophisticated. It used 17" narrow high-pressure tires and had front and rear suspension. The small wheels made room for carrying quite a bit of cargo over the front and rear wheels. (I knew a college physics professor, an all season cycle commuter like Wilson, who carried a 55 lb. filing cabinet on the back of his Moulton.) The Moulton could also be folded in half for storage and transport.

So, even though he was riding the best engineered commuter bicycle, he still felt there was a lot of room for improvement.

As Wilson was about to leave the UK for the USA and his job at MIT, he found out he would not be able to take his savings with him.So in 1967 he took his savings and organized an international competition for man-powered land transport. There were 73 entrants before the judging in 1969.

A summary of the results can be found in the magazine:

Engineering (London) vol. 2071, no 5372, 11 April 1969, pp. 567-573

The winning design was from W. D. Lydiard, a British aerospace engineer. Not only did he submit a paper design he build an actual prototype of his Mk.3 version. He called this version the Bicar.

The Bicar was an enclosed recumbent bicycle that used 16" wheels. Lydiard invariably encountered what I call "the recumbent bicycle problem", that being, for a front steered recumbent bicycle, the pedals want to be in the same location as the front wheel for an ideal weight distribution. He solution was to use an non-circular, elongated pedal path located above the front wheel. the pedals moved in near linear tracks and were attached to connecting rods that pulled on a conventional crank. This mechanism is what I refer to as a "oscillating treadle".

The post listed below discusses linear pedal motion in some depth.

https://www.blogger.com/blogger.g?blogID=7497191769424400596#editor/target=post;postID=5532337496842064005;onPublishedMenu=template;onClosedMenu=template;postNum=9;src=postname

Lydiard encountered interference with the pull rods when he put his feet on the ground through the flaps in the body, so he also presented a Mk. 4 version that used what I refer to as a constant-torque treadle.

Wilson was quite taken with the use of an elongated pedal path to minimize foot-front-wheel interference and came up with over a dozen sketches of different concepts, eventually detailing the design show below.

In 1973 Wilson was approached by Frank Rowland Whitt, a chemical engineer and a writer of technical articles for cycling publications. Whitt had gathered material for a book about Bicycling Science and he approached Wilson in hopes that he could help him get it published. Wilson in turn approached MIT Press and they agreed to publish it if Wilson would be a co-author.

The first edition was published in 1974. It was the first technical treatment of bicycle technology since Archibald Sharp's Bicycles and Tricycles published in 1896 and republished by MIT press in 1977. At last, human-power vehicle enthusiasts had a technical reference to aid in their research and designing. The technical bible had arrived and has only gotten more comprehensive with each edition.

Soon to be in it's forth edition, it is MIT Press's best selling publication.

In the mid 70's Wilson was contacted by a California bicycle mechanic named Frederick Willkie regarding the design of a recumbent bicycle and Wilson sent him several sketches. What resulted in what Willkie call the Green Planet Special 1 shown below.

The GPS1 was very similar to the Ravat recumbent of the 1930's.

Willkie found the GPS1 uncomfortable to ride and asked for some modification suggestions. Wilson told him to lower the pedals in front of the front wheel, locate the handlebars below the legs directly on top of the fork and lean the seat back. The GPS2 was born.

For reasons not revealed, Wilson purchased the GPS2 form Willkie. He made subsequent modifications and the Wilson-Willkie recumbent bicycle was created. Wilson added a number of creative features to the WW. Loops attached to the pedals that allowed one to ride with dress shoes, a large luggage box behind the seat and a hammock style seat.

By 1976, Wilson riding the Wilson-Willkie recumbent became the poster child for a better bicycle, at least in the USA. He was featured in newspapers, magazines and a commercial for creativity by the Mobile Oil Company

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lYbfz4vCczg

I sure the irony of a man riding an alternative to the automobile being showcased by an oil company was not lost on Wilson.

Wilson teamed up with Harold Maciejewski and Richard Forrestal to investigate making commercial recumbents.

The Avatar 1000 thus followed the WW.

The Avatar 2000 went on sale in 1980 and was the first commercial recumbent since the Second World War. ( The Hypercycle, being a knock-off of the Wilson-Willkie quickly followed.)

I have ridden s.n.85 Avatar 2000 for 35 years and I must say it is the most comfortable bicycle and recumbent that has ever been manufactured. The only negatives I have encountered are the difficulty in transporting a bicycle with a 63" wheelbase and a lightly loaded front wheel which can wash out on slippery surfaces.

Wilson generated a chart comparing the weight distributions of various upright and recumbent designs.

The ideal appears to be having between 36 & 40% of the vehicle and rider weight on the front wheel.

It is interesting to note that if one used a 16" and was to allowed an intermediary bottom bracket with sprockets on both sides, ( as the GPS1 and GPS2 had) then the wheelbase could be made 8" shorter than the Avatar 2000 and the front-wheel weight distribution could be increased the 35.5%, getting very close to the idea.

In later years Wilson did not commute on an Avatar 2000. When he rode to the campus at MIT he had to carry his bike up quite few flights of stairs to his office. The Avatar 2000 was much too cumbersome for that task so he rode more compact recumbents of his own design.

The second picture was probably Dave's last recumbent and is of interest because it uses a timing belt to connect the pedals to the intermediary bottom bracket.

I was first introduced to Wilson in 1970 reading his 1968 article "Where Are We Going In Bicycle Design?" reprinted in Harley M. Leete's "Best of Bicycling" book.

I bought the first edition of "Bicycling Science Ergonomics and Mechanics" in 1974.(I subsequently bought the second and third editions and will buy the fourth edition when it is published next year).

I started communicating with him in 1976 while in grad school requesting more information about his recumbent designs.

In 1989 he edited my article on rear-steering recumbent bicycles published in "Human Power", the magazine of the International Human-powered Vehicle Association (IHPVA).

He sent me over a dozen of his designs for linear pedaling recumbents.

I met Prof. Wilson at the 1990 IHPVA speed championships held in Portland Oregon. I believe he was the president of the IHPVA at that time.

And he endorsed the Lefthandedcyclist blog and his friend and publisher Richard Ballantine expressed interest in publishing a collection of my posts.

Prof. Wilson, the bicyclist and human-powered vehicle builders of the world are greatly in you debt.

Dr. Recumbent, we solute you!

Hephaestus

Professor David Gordon Wilson of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, on a Tricanter machine bicycle riding around the University of Canterbury campus in Ilam.

Creator: Christchurch Star

Thursday, November 29, 2018

Aerion: An Optimized All-weather Ped-electric Trycicle

http://lefthandedcyclist.blogspot.com/2012/01/rx-for-healthy-commute.html

1. The vehicle should have three wheels for stability on slippery surfaces.

2. It should place the rider's head at the height of a typical automobile.

3. It should be narrow enough to comfortably fit in a bike lane. I can be more specific on this. It should fit between barriers spaced 36" apart, so assume a maximal width of 34".

4. It should not overturn when cornering. Assume a tipping resistance of 1 gee.

4. It should be enclosed to protect the rider from the elements.

5. And for traction on slippery surfaces, it should drive two wheels.

Now if the vehicle is a static tricycle point 2 and 3 are at odds with each other. High enough rider and wide enough to not tip over in turns results in a vehicle that has a width of about 48".

The solution to this contradiction is a leaning tricycle.

http://lefthandedcyclist.blogspot.com/2012/02/drymer-and-varna-lean-forward.html

http://lefthandedcyclist.blogspot.com/2015/12/the-velotilt-pedal-powered-commuter.html

When correctly designed, leaning trikes can be balanced just like bicycles. Like bicycles, the most difficult task is getting started from a stop. One has to develop balancing speed often with one pedal thrust to avoid tipping over or having to put a foot down and start again.

Problems appear when the leaning trike is enclose in a body that interferes with the action of starting.

To remedy this potential problem the vehicle need a mechanism to lock-up the leaning for starting, and stopping. The locked-up mode could also be used in slippery conditions when balancing is not practical. You now have two modes of operation, balancing and being stable. The rider has to switch modes and decide when to do so.

Refer to the Velotilt design where the leaning needs to be locked up when the rider gets into the vehicle and starts moving or when the vehicle is stopping.

I discussed the problems I had starting and stopping my EcoVia trike in the post below.

http://lefthandedcyclist.blogspot.com/2015/08/transcending-pedicar-ecovia-epilog.html

When a fellow HPV-er tried to ride the EcoVia he pointed out the average rider would have trouble mentally switching from one mode to the other. I could not disagree, having once forgotten that I was in the balancing mode and thinking I was in the static mode. This resulted in a swerve that may have ended my HPV career had there been any other cars near me at the time.

So how to address this problem?

I believe you must have the static mode for starting, stopping and slippery conditions. The balancing mode is the most problematic so eliminate that. Since you still need to lean the trike to prevent tipping over in corners, make it controlled by the rider by means other than balancing.

Now since accelerometers, controllers and stepper motors are inexpensive, the logical approach for controlling lean for an electric vehicle is computer control, with it being transparent to the rider. Since lean angle is a function of radial acceleration, which in turn is a function of steering angle and vehicle speed, the necessary calculations are relatively simple.

Lean control for non-electric vehicles is more problematic.

GM's Lean Machine from the 1980's used foot pedals, since the vehicle as gas-powered.

One could combine lean control and steering into one action. I tried that with the first version of the EcoVia, but the approach introduced bump-steer with disastrous consequences.

http://lefthandedcyclist.blogspot.com/2012/08/ecovia-healthy-electric-hybrid-vehicle.html

Or one could use dual-control that used two hand motions, one for steering and one for leaning. The Tripendo uses this approach with apparent success. It employs two long levers. One does the steering and one does the leaning. The rider continually adjusts both to keep the trike stable.

Dual control could be used without requiring continuous lean adjustment. For example, the MK3 version of my EcoVia has a c.g. height of approx. 23 in. an a track of 30". This allows for a .43 gee turn without needing to lean.

For a vehicle that leans by having its wheels move essentially vertically, staying parallel to the vehicle, like the Toyota iRoad above, the relations below apply:

The first equation calculates the relation between width, height and lean angle at the limit of tipping. The second equation calculates the relation between the width, height and lean angle that will resist one gee laterally without tipping.

Interestingly, the lean angle for this condition is not a function of w (track) or h (cg height). It ends up being 26.6deg. Not surprisingly, The lean angle of the iRoad is about 26deg. And the iRoad width is about 34"

The cg. height for the above conditions is a function of the lean angle and the effective track, w. If the actual track is 30", the effective track is approx 2/3 of that for an equal-wheel-load configuration or 20". For a 20 track the required c.g. height is 25".

Let us compare the gee limits for several configurations with this geometry.

1. Statically, without any lean, it would take .4 gees to tip over.

2. For balanced leaning, it could withstand .5 gees. The vehicle would have to lean 45deg to resist 1 gee.

3. If the vehicle had four wheels where the front and back track was equal, it could withstand .6 gees. The track would have to be 50" to resist 1 gee statically.

4. And with the lean locked at its 26.6 deg limit, it could withstand 1 gee.

Clearly, for a given track width, a tricycle with controlled leaning gives the greatest resistance to tipping.

So our optimal all-weather ped-electric trike will have controlled leaning where the leaning is determined by computer.

What about the wheel layout? Should it be a delta trike or a tadpole trike. Due to drive-train complexity I will eliminate the tadpole configuration where the front wheels drive and steer. That means that if the two front wheels drive, the single rear-wheel steers. (Like the iRoad).

Below is the EcoVia Mk3. The long lever controls the leaning while steering is located below the seat.

The biggest advantage of the delta configuration is the pedals can overlapped with the front wheel to produce a very short vehicle. The vehicle can be lighter weight because the structure supporting the front wheel can also support the pedals. Along with these advantages comes three disadvantages. The steering lock is limited. Not enough to be a problem for normal turns but enough to prevent tight turns. Only one wheel is available up front for braking where the load is transferred to during hard braking. Lastly, the steered wheel is the first wheel to encounter obstacles like railroad tracks. The obstacles can perturb the steering and unexpectedly change vehicle direction.

Below is the EcoVia Mk1

The biggest advantage of the tadpole configuration is it doesn't suffer from the three issues plaguing the delta configuration. On the other hand, the package is longer that the delta configuration because the pedals are on one end and the steered wheel is on the other. The space between the seat and the rear wheel could be used as a trunk. And there is the issue with rear-wheel steering. Since the controlled leaning approach does not involve balancing, this should not be a show-stopper. After several communications with Jim Kor of Urbee fame, he described his approach to make his rear steering stable. The Urbee without body is shown below.

I believe despite its problems, the tadpole configuration wins out.

Below is a drawing and photo of the Cyclodyne, a tadpole trike from the early 1980s that was capable of cruising at over 30mph. The Cyclodyne, of all the commercial human powered vehicles, came the closest to harnessing the potential of human power as a transportation alternative.

To resist tipping rider's head height was about 39" and the vehicle width was about 48". Roll-over resistance as at least 1gee. While the rider's head height was acceptable, being comparable to a sports car, the width was too wide to fit comfortably on a road shoulder.

Had it been made a quad by adding a fourth wheel, the width could have been reduced to the target 34" and speed would have been increased as well, making it a very practical commuter vehicle. But the fourth wheel would prevent it from being considered an electric bike if a motor was added.

Adding controlled leaning could have reduced the vehicle width, increased visibility by raising the rider's head height and allowed it to be electrified. An optimal all-weather tricycle configuration.

Even though it only exists as a few equations and a few crude sketches, I have a need to give a name to this all-weather, ped-electric, fixed-leaning, front-driving, rear-steering tricycle. I will call it the Aerion. (Aerion is also the name of an aviation company developing a supersonic business jet).

I have a bias for the Toyota iRoad. My first configuration in 1990 for the EcoVia was a front-driven, rear-steered leaning configuration. I was not using controlled leaning but was balancing the vehicle and I could not make the rear-steering stable. More than two decades later, electronic controls allow the iRoad to do what I couldn't and reap the benefits of an optimal configuration.

Hephaestus