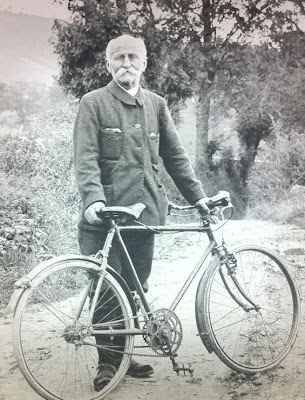

Paul de Vivie, who wrote under the nom de plume of Velocio, is the patron-saint of cyclotouring. In addition, anyone who rides a derailleur bicycle owes him a huge debt of gratitude for his tireless efforts to develop and refine this method of shifting. He started his life of cycling riding a high-wheel bicycle at the age of 28 and ended it riding a multi-speed safety bicycle. His untimely death, at the age of 77, occurred after being struck by a streetcar while walking across a street.

Living in Saint Etienne, a very mountainous area of France, Velocio was disposed to taking very long rides. He was in a perfect location to devote his life to developing the then-non-existent sport of bicycle touring and refining the bicycle for long distance use, especially in the area of multiple gears.

Velocio contributed to cycling in at least four major areas.

Most significantly, he inspired countless others to take up the sport of cycling, both through example and through his writings in his magazine Le Cycliste. He wrote about how cycling enhanced the senses by describing the beauty he experienced on his rides. Averaging over 12000 miles a year and routinely taking rides in excess of 400 miles at a time, detractors accused Velocio of being a pedaling automaton, oblivious to his surroundings. But regarding one early morning excursion as the sun was coming up he writes “A shaft of gold pierced the sky and came to rest on a snowy peak, which, moments before, had been caressed by soft moonlight”. Clearly, he was very attuned to the world through which he pedaled. In his magazine he also discussed cycling technique and debated proper equipment.

He developed cycle touring into a discipline that allowed riders to achieve optimal performance and maximum enjoyment on their excursions. His seven rules for the long distance cyclist are as relevant today as they were 100 years ago.

Through research and experiment he refined the bicycle for long-distance riding. He is most famous for being a zealous advocate for multiple gears, but he also experimented with different tire diameters and widths in an effort to balance comfort with performance. Two of his specific contributions made the modern derailleur possible. Contrary to the prevailing wisdom that the chain needed to be parallel to the cogs and chainrings to drive properly, Velocio found that the chain could be slightly angled to the sprockets and still transmit power efficiently. His second contribution was to insert a linkage into the rear derailleur to reverse its action. Pulling the shift cable in previous derailleurs caused the chain to move from the larger to the smaller sprockets, essentially downhill, the easier of the two directions. A spring was used to reverse the chain motion causing it to climb up hill. Velocio’s reversing linkage allowed the chain to be pulled uphill, synchronizing the greater input force with the greater requirement. The spring to reverse the motion was aided by the chain going downhill, and, as a result, could have its required force

reduced.

Velocio also experimented with lever-drive bicycles. Starting in 1904, he rode a Svea for several seasons, about 1/4 of his time on the bicycle. Bicycles like the Svea, with lever drives connected to over-running clutches, reportedly work very well for steep climbs and this is probably why he found one useful. Below is one of his own lever-drive designs. Depending on where you placed you foot on the treadles, you could vary the effective gear ratio of the drive. A cable connected from one treadle to the other insured that the non-driving treadle moved up while the driving treadle moved down.

reduced.

Velocio also experimented with lever-drive bicycles. Starting in 1904, he rode a Svea for several seasons, about 1/4 of his time on the bicycle. Bicycles like the Svea, with lever drives connected to over-running clutches, reportedly work very well for steep climbs and this is probably why he found one useful. Below is one of his own lever-drive designs. Depending on where you placed you foot on the treadles, you could vary the effective gear ratio of the drive. A cable connected from one treadle to the other insured that the non-driving treadle moved up while the driving treadle moved down.

And lastly, and maybe most significant for current times, Velocio demonstrated that older athletes could still perform at high levels. On the first Velocio Day in 1922, where 163 cyclists converged on Saint Etienne to honor de Vivie and race up the Col du Grand Bois, he won the 60-70 year old age class! Velocio advised “Every cyclist between 20 and 60 in good health can ride 130 miles in a day with 600 feet of climbing, provided he eats properly and has the proper bicycle”. Keep in mind too that these cyclists would be riding on dirt roads and not rolling along at the speeds we associate with paved roads.

Now a person can buy a bicycle for many reasons. They need it as a means of transportation. They want it for exercise. They want it as an object de arte. They want it to explore their surroundings under their own power.

As a freshman in college, I wanted a new bicycle because I was fascinated by the minimalist beauty of a true racing bike. After reading R. John Way’s cycling books and marveling at Daniel Rebour’s component illustrations, I learned a new word, Compagnolo. This was several years before the bike boom hit in the early 1970’s. So amid cries of “You are a grown man and you are buying a bicycle?”, I forsook my old Schwinn Varsity for a very-Spartan, all-white Raleigh Professional. The speed was intoxicating. I raced trucks across the viaducts spanning Milwaukee’s industrial valley but carried the bike across streets because I was afraid of glass puncturing the sew-up tires.

After the novelty of the technology and the speed wore off, I was still experiencing the excitement of exploring under my own power. In Milwaukee, riding east to the lake and then up along Lakeshore Drive past Doctor’s park and points north or going southwest to Lake Geneva, the smooth roads that never seemed to end made it difficult to turn around and head home. So many roads to explore…

In Madison the biking was even better. A mile from campus and into the arboretum took you for a quick trip to Paoli. You could pedal up to Devils Lake and a ride on the little Merrimac ferry or ride over to the Elroy-Sparta Trail through Amish country. With the plethora of little farm roads crisscrossing southern Wisconsin, it was always easy to find a road that was good for bicycling but was light on auto traffic. And there was the bike racing during the summers…

I admit when I arrived in Seattle after graduate school, I was disappointed with the cycle touring in the surrounding area. The roads the cyclists used were much more scenic than those of Wisconsin, but there weren’t as many and, if they went any distance, you found yourself sharing them with cars.

I got used to things but I was no longer bike racing and got bored with the weekend touring. For a change I decided to pluck down a king’s ransom for a recumbent bicycle, an Avatar 2000. I expected great gains in my speed and was very disappointed when I found out I was significantly slower than an upright bicycle, and that was on the flats! What it did provide, however, was unexpected comfort. After about five hours on the upright, things got uncomfortable and I rode an Exxon Graftek frame which attenuated a lot of the road vibration. With the Avatar, no numb crotch, no numb hands, no tired back. So I started taking longer rides and my bicycle exploring had a renaissance. I rode that Avatar for 22 years and logged more miles on it than any other bicycle I owned. And each time I took out the upright for a ride, the lack of comfort brought me back to the recumbent.

My son Kyle got into bicycling on his own and from a different direction. There is a rather elaborate dirt-trail system near our house (Now the Paradise Valley Conservation Area) that he and his friends rode since he was in junior high school. When he went up to Western to study Industrial Design, there was a strong mountain-biking community on campus and so he continued to refine his technical mountain biking skills. We had a family bike that happened to be a mountain bike and I used it when I went up to Bellingham to ride Mount Galbraith with him. I crashed twice in the first 100 yards and walked through much of the technical sections of the park. I just couldn’t see why someone would want to ride slowly on dirt when you could go fast on pavement, and a lot of the mountain bikers around me didn’t look all that fit. He did take me on a very scenic but unexpectedly steep climb that I ended up walking the last 100 yards. Despite all this, it was nice seeing cycling from his perspective, even if it wasn’t for me.

Several years passed and I was going to give Galbraith another try. I popped the knobbies on the family bike and took it out for a spin on a Labor-Day morning. Several mountain bikers road past my house and I decided to follow them (Unbeknownst to me at the time, they were coming from the trail system my son and his friends frequented). They turned on to a trail that I had ridden past many times on my road bike but had never ridden on myself. The trail headed east and up a long hill that was steep enough to still be in the shadows. As I reached the crest and rode into the sunshine, I was facing a beautiful view of the Cascade Mountains. I had never seen this area before and it was in my own back yard. A mountain bike would let me explore new trails and I wouldn’t be sharing them with cars. I stopped to remove some layers after the exertion of the climb and subsequently lost track of the other cyclists, but it didn’t matter. I was hooked and I needed to find out where the trail I was on led.

This was an epiphany for me. I knew now that there was more to mountain biking than the technical riding my son practiced. If you took a road cyclist and put him on a mountain bike he could still do exploring and point-to-point riding. I became what I would later christen a “dirt-roadie”.

And with that I knew that western Washington was a very good place to be a dirt-roadie. Between forest service roads, logging roads and abandoned railroad right-of-ways, like Ironhorse State Park, there were many opportunities to go exploring on dirt.

One of the rides I would take was on private forest land (now closed to cyclists). After five miles of climbing switchback logging roads in my lowest gears, I arrived at pristine alpine lake. Since there were amost no cars to be seen on this ride, it was easy to imagine being back in time 100 years and riding the alpine regions of France like Velocio. Roads where multiple gearing and a cushioned ride were indispensible.

My favorite rides are along the abandoned Milwaukee Road railroad line through the Ironhorse State Park. I love the history associated with the railroad and riding through the tunnels along the route makes the rides unique. Using this route, with a few paved-road connectors, I can ride from home to the Columbia River. As a dirt-roadie, you have got to love western Washington.

Credit for my exposure to Velocio in my formative cycling years goes to an article by Clifford Graves in his May 1965 article for Bicycling Magazine, which was later compiled in the book “The Best of Bicycling”. Frank J. Burto’s book “The Dancing Chain” gives an excellent history of the development of the derailleur and Velocio’s contributions to that development. (Thanks Jerry for turning me on to this one!)

Oh, and Velocio’s seven rules for cyclotouring…

1. Keep you rests short an infrequent to maintain your rhythm.

2. Eat before you are hungry and drink before you are thirsty.

3. Never ride to the point of exhaustion where you can’t eat or sleep.

4. Cover up before you are cold and peel off before you are hot.

5. Don’t drink alcohol, smoke or eat meat on tour.

6. Never force the pace, especially in the early part of a ride.

7. Never ride just for the sake vain glory.

To quote Clifford Graves, "Velocio-the cyclists of the world salute you".

Hephaestus